Will The U.S. Supreme Court Hold Trump To Its Own Standard?

Pres. Donald J. Trump plans to appeal a lower court decision finding he violated the First Amendment by retaliating against the Associated Press for failing to recognize the Gulf of America.

The issue of whether the Associated Press newswire service has a First Amendment right to attend White House events is headed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

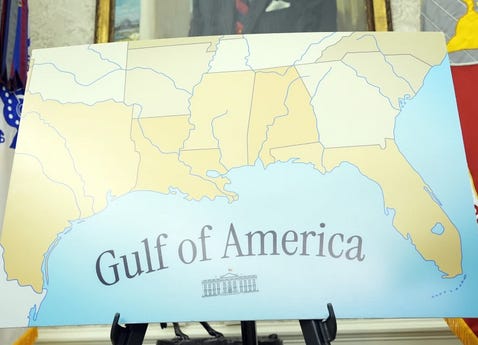

Pres. Donald J. Trump signed an executive order immediately upon taking office, changing the Gulf of Mexico’s name to Gulf of America.

A valid executive order has the force of law unless it is found to b…