Why Can't We Watch The Dugan Trial?

An outdated 1946 rule bars the livestreaming and broadcasting of federal criminal trials, including the important, highly political trial of Milwaukee, WI, Judge Hannah Dugan.

*Milwaukee County Judge Hannah Dugan was convicted of felony obstruction of federal law enforcement officers on Dec. 18, 2025 and resigned on Jan. 3, 2026 to avoid impeachment proceedings.

In 1946, Frank Capra’s film, “It’s a Wonderful Life,” premiered.

It was post-WWII, and the newly formed United Nation’s held its first proceedings in New York City.

And that was the year that a new rule, promulgated by the U.S. Supreme Court, went into effect. Eighty years later, that rule is still in effect, denying Americans the right to see important federal court proceedings live on television or the internet.

Rule 53 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure states that the court “must not permit” the taking of photographs in judicial proceedings or the broadcasting of judicial proceedings from the courtroom.

This antiquated rule is why the public cannot observe the trial of Wisconsin Judge Hannah Dugan unless they are physically in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and able to get to the courtroom. (What if you’re incapacitated? What about the Americans with Disabilities Act?)

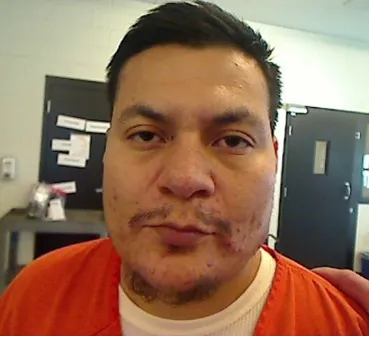

Dugan is a Milwaukee County circuit judge who faces charges of obstruction and concealing an undocumented immigrant to prevent his arrest by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents.

The trial reflects a major contest between judges, many appointed by Democrats, specifically for the purpose of thwarting the GOP administration of President Donald J. Trump, and Trump’s sweeping immigration crackdown.

A similar case involved Massachusetts Judge Shelley M. Joseph who was charged criminally with helping an illegal immigrant evade ICE agents in 2019. The charges were dismissed. A supposed independent investigation recently resulted in a recommendation that the judge be publicly reprimanded.

The Dugan Trial

On the first day of the trial, Assistant U.S. Attorney Keith Alexander said Dugan remarked, “I’ll do it. I’ll get the heat.”

Dugan said this after she was informed that five ICE agents were outside her courtroom, in the hallway, with an undocumented immigrant.

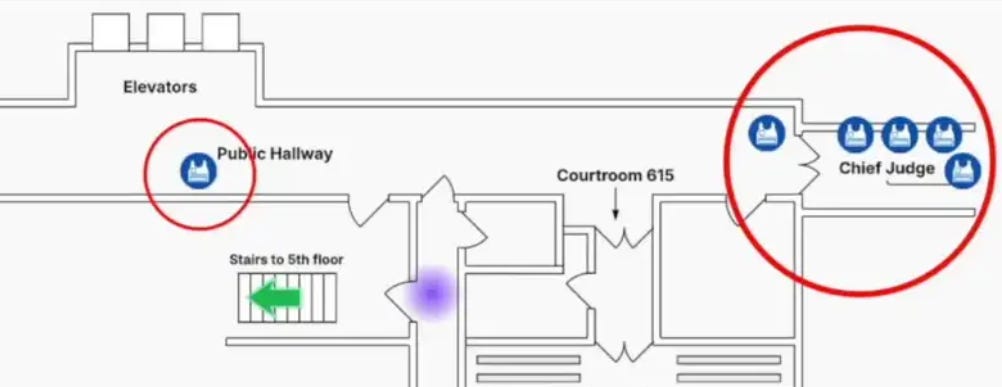

In her judicial robes, she confronted the ICE agents in the hallway and told them to go see the chief judge down the hall. The chief judge had earlier informed Dugan and court personnel that ICE agents could legally conduct enforcement actions in the public areas of the courthouse.

Dugan called the case of Eduardo Flores-Ruiz, 31, earlier than scheduled.

Alexander said the parties in the courtroom discussed whether Flores-Ruiz could evade the ICE agents, and Dugan directed him and his attorney to a non-public hallway leading to a stairwell that led to an exit in the basement.

A video shows that the hallway also led to a second door that led to a public area. Flores-Ruiz and his public defender went through the public door and were followed by ICE agents out of the courthouse.

Flores-Ruiz fled on foot, and the agents were forced to chase him before they could apprehend him.

“They did not expect a judge, sworn to uphold the law, would divide their arrest team and impede their efforts to do their jobs,” Alexander told the jury.

Flores-Ruiz faced charges of illegally re-entering the U.S. after a prior removal, along with charges of strangulation and suffocation, battery, and domestic abuse. He pled guilty and was deported last month.

Dugan initially claimed judicial immunity, but U.S. District Judge Lynn Adelman ruled there is no general judicial immunity from criminal charges simply because some of the alleged conduct occurred in the court of judicial duties. Dugan’s defense currently seems to be that she lacked intent, which lends itself to questions of credibility.

It’s hard to evaluate Dugan’s credibility without seeing the witness in court.

$149.00 a year

If you happen to live in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, you potentially could attend the trial in person, or at least find a seat in an “overflow” room.

Otherwise, you must depend on media accounts. But that option may be limited. Milwaukee’s major newspaper, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, requires a $149 / year annual subscription to read its in-depth coverage of the trial. Many major national publications also require paid subscriptions.

The public is largely relegated to free news sites, which might limit coverage to short summaries and general assignment reporters who work for local television and radio stations.

Rule 53

Why has Rule 53 survived for 80 years when it creates a lack of transparency in the federal court system? There are legitimate reasons to close a courtroom, such as to protect witnesses from intimidation. But there is no legitimate reason for a default rule that closes all courtrooms.

Court officials often say the basis for Rule 53 is to protect the dignity of the proceedings, but there is no reason to think the proceedings are less dignified because people can see what is transpiring.

Most importantly, there are many reasons to make open hearings the default in the U.S. court system.

Perhaps the most compelling reason is that Americans have a fundamental right to access criminal proceedings to ensure fairness and accountability.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled 7-1 in Richmond Newspapers, Inc. v. Virginia (1980) that the public has a First Amendment right to attend criminal trials, noting that, when the nation was founded, criminal trials both here and in England had “long been presumptively open.” The majority said closures are unconstitutional unless there is an “overriding interest” and no less restrictive means.

What does ‘open’ mean?

It is clear what it means to close a courtroom, but what does it mean to open a courtroom? There is no reasonable way to interpret opening a courtroom with a prohibition on broadcasting and streaming criminal trials.

Meanwhile, secrecy is very convenient for the third branch. The public cannot assess the fairness and accountability of criminal proceedings when they are effectively barred from seeing the proceedings. This protects federal judges, who serve lifetime appointments, from accountability.

It is immediately apparent when a judge falls asleep on the bench, or engages in misconduct by failing to be courteous, impartial, non-partisan, or unfair.

Is The Judge Partisan?

The public has a special reason to assess how Judge Adelman comports himself in Dugan’s case.

Adelman, who was nominated by former Democratic President Bill Clinton in 1997, was admonished by the 7th U.S. Court of Appeals in Chicago in 2020 after three judicial complaints stemming from an article he wrote, entitled, “The Roberts Court’s Assault on Democracy,” published in the Harvard Law & Policy Review.

In the article, Adelman described the Republican Party as having become “more partisan, more ideological and more uncompromising.”

The 7th Circuit concluded Adelman’s criticism of U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts and GOP policy positions “do not promote public confidence in the integrity and impartiality of the judiciary.”

Will Adelman be fair and impartial in Dugan’s case? Doesn’t the public have a right to know?