Inside The Book 'How To Kill A Federal Judge'

The book that landed a 72-year-old author in federal prison is hostile but far from terrifying. It is an expose of the brutality of federal courts, with cartoonish, sometimes witty drawings.

Robert Phillip Ivers, 72, wrote a book entitled, How to Kill a Federal Judge, and printed it out on September 3 at a public library in Wayzata, Minnesota.

A librarian reported it to police, and he was arrested, incarcerated, taken to a hospital for a flare-up of obstructive coronary artery disease, and returned to jail.

He has been there since, allegedly because he is too dangerous to release.

On September 11, Ivers was indicted by Minnesota’s U.S. Attorney’s Office for threatening to assault and murder a federal judge and a Supreme Court Justice, and for interstate transmission of threats to injure others, including a defense attorney. He faces years in prison, probably a life sentence.

This week, I reviewed Ivers book, and it appears to be well within the scope of the First Amendment. His treatment reflects a federal judiciary that is paranoid, defensive, and more than willing to sacrifice the principle of freedom of speech to feel better about driving home at night.

The scenario is surreal.

The First Amendment is supposed to protect authors. Historically, it has protected books that instruct readers on how to terrorize and kill people. Stephen King voluntarily withdrew his book Rage, about a psychologically troubled high school student, from the market after it was linked to at least three actual school shootings.

Moreover, federal judges are there to protect - not subvert - the U.S. Constitution, the “supreme law of the land.”

In its 1969 ruling in Watts v. United States, the U.S. Supreme Court held that only “true threats” are outside ordinary First Amendment protections.” The defendant in that case was a pacifist who said, “If they ever make me carry a rifle, the first man I want to get in my sights is L.B.J.” His conviction for threatening the president was reversed on the grounds that he was merely engaging in “political hyperbole.”

Other established precedent establishes that a real threat must be imminent. Ivers’ book was compiled over a period of years. Would a reasonable person consider a “threat” made five years ago an imminent threat?

Yes, Ivers makes veiled “threats” that reflect his brutal treatment in the federal court system. But it’s nowhere close to a “terrifying 236-page manifesto,” as described by Minnesota’s Acting U.S. Attorney Joseph H. Thompson.

What is the book…

Ivers’ book is mostly a collection of court documents related to his various cases, with notes by Ivers in the margins.

He makes dramatic warnings about the likelihood of dire consequences for judges who continue to persecute, er, prosecute him.

And he offers random thoughts and observations. For example, Ivers ruminates about how to fix the antiquated federal judicial system. He proposes that trials be held before a panel of legal experts rather than “outdated judges driven by bias and personal agendas.”

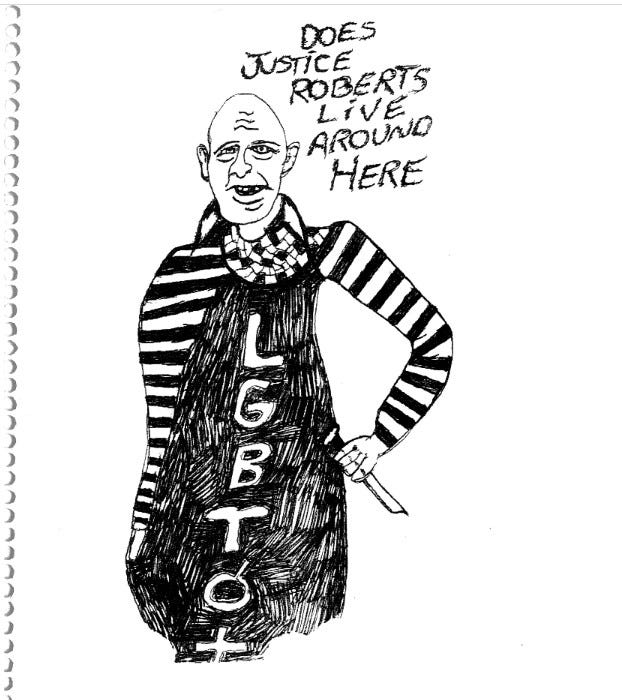

Much of Ivers’ prose is satire or political hyperbole. Consider his alleged threat to U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Roberts, who was widely criticized as anti-trans for upholding a ban on gender-affirming care for minors. It’s a hand-drawn picture in which a seemingly smiling guy with a knife asks, “Does Justice Roberts live around here.”

Ivers’ book recounts the all too familiar story of the unwelcome self-represented plaintiff in federal court. He is subject to inscrutable and multiple sets of different rules for which he receives no guidance. One mistake can be fatal. Worse, he faces an unfriendly judge who much prefers dealing with fawning, subservient lawyers to everyday people in distress.

Initially, Ivers sought to recoup $100,000 left to him in 2015 through an insurance policy by a deceased friend. U.S. District Judge Wilhelmina Wright denied his request for a jury trial as untimely and dismissed the case after a two-day bench trial.

‘Imagined‘ Threats

In 2018, Ivers consulted two volunteer attorneys from the Federal Bar Association’s Pro Se Project. They said a new case could not be brought to claim the insurance money due to the terms of Wright’s dismissal. Ivers angrily complained that Wright “stole my life from me,” “stacked the deck,” and that he had “imagined 50 ways to kill her.”

Incredibly, the attorneys reported Ivers’ “imagined” threats to kill Wright to the court.

“People yell ‘kill the umpire’ all the time at baseball games. Should we arrest them?’” - How Kill A Federal Judge.

Even though Ivers’ threat was a figment of his imagination, he was convicted of one count of threatening to murder a federal judge and a second count of interstate transmission of threats, and sentenced to 18 months in jail.

Incredibly, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit in St. Louis in 2020 affirmed Ivers’ conviction and 18-month sentence, holding that Ivers’ statements to the volunteer attorneys were not protected by attorney-client privilege. The appellate court held that the attorney/client privilege applies only to communications for legal advice.

The U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear Ivers’ appeal, which asked whether a confidential attorney/client phone call to get legal advice is protected in its entirety by the attorney-client privilege.

“Anyone reading this, can you believe this bullsh-t!!!” - from How to Kill A Federal Judge.

There is much more to this story, of course. After his release, Ivers left what prosecutors described as a “profanity-laced” voicemail on his probation officer’s telephone that was held to violate the terms of his release. He was sent back to jail for two years.

But to get back to the book.

Ivers’ court-appointed counsel, Brett D. Kelley, of Kelley, Wolter & Scott in Minneapolis, is considering filing a First Amendment challenge to the latest charges against Ivers. He said Ivers’ book was introduced as evidence in 2022 case and Ivers has never posed a real threat to anyone in the judiciary. Kelley is worried another jail sentence for Ivers, who is in ill health, will be the equivalent of a death sentence.

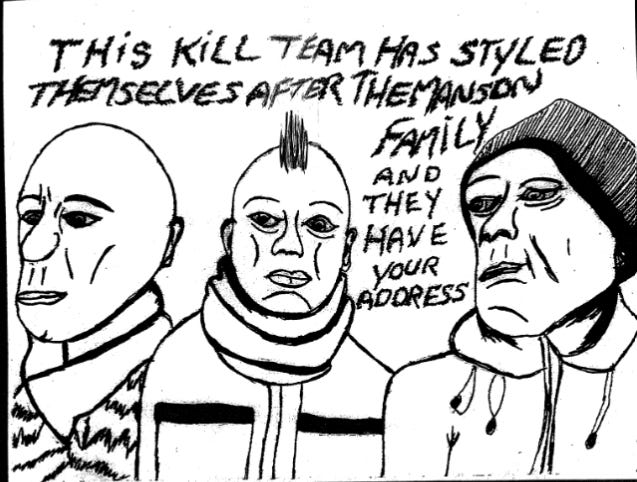

The following images may be unsettling and disturbing in the context of a book about killing federal judges but it is hard to see how they can be characterized as illegal threats:

Robert Phillips Ivers clearly hates federal judges. Perhaps this is understandable given the fact that he lost a small fortune due to an untimely request for a jury trial, and was jailed for four years because of imaginary thoughts. But he is now in his 70s and he is suffering from coronary artery disease.

Should he receive the equivalent of a life sentence for writing a book?

Assistant U.S. Attorney Melinda Williams, who is prosecuting Ivers, failed to return an email asking her to cite the pages in Ivers’ book “that your office has concluded constitute a criminal threat.” If she responds, her response will be included here.